The neuroendocrine system is the body’s communication network. It is made up of specialised glands, which make and release hormones into the bloodstream, in response to different situations and signals, that can come from both inside and outside the body. These signals reach every organ and tissue in your body including the brain.

A gland in the endocrine system is made up of groups of cells that function to secrete hormones., while a hormone is a chemical that moves throughout the body to help regulate emotions and behaviours. When the hormones released by one gland arrive at receptor tissues or other glands, these receiving receptors may trigger the release of other hormones, resulting in a series of complex chemical chain reactions. The endocrine system works together with the nervous system to influence many aspects of human behaviour, including growth, repair, reproduction, and metabolism. And the endocrine system plays an integral role in e-motion states. The glands in men and women differ, hormones also help explain some of the observed behavioural differences between men and women. Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus, right?

Bottom line is, every single day your neuroendocrine system is pumping out hormones to help control and regulate many body functions.

But what are hormones?

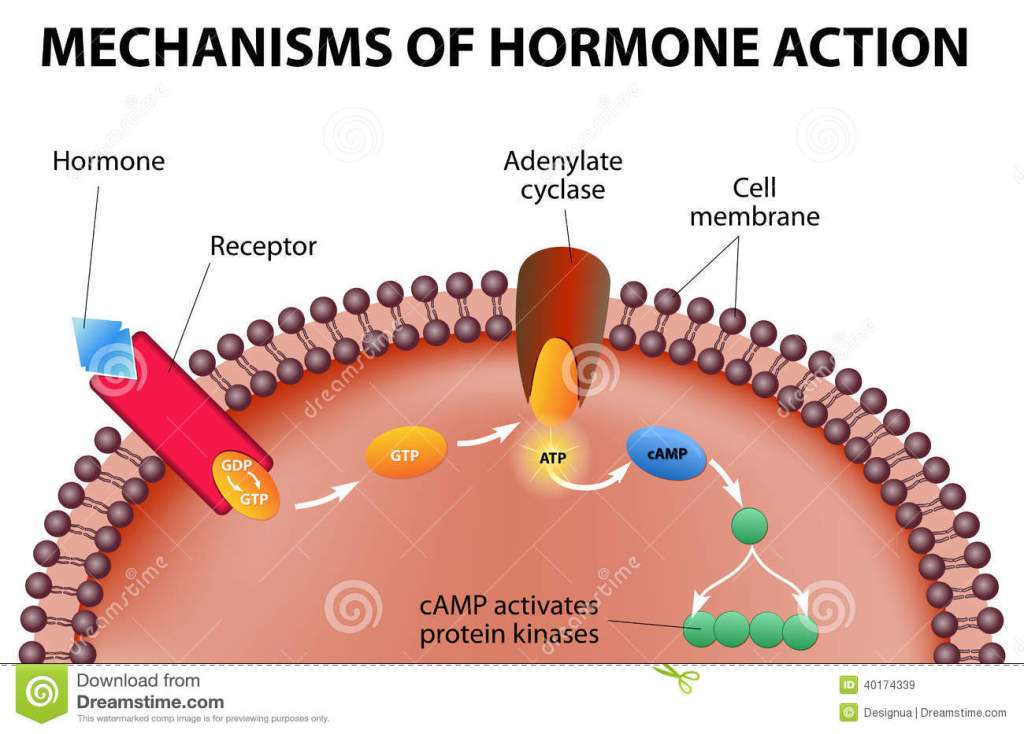

Essentially they’re chemical messengers that travel through the blood to different parts of your body. They signals the body to act in a certain way, so to speak. Hormones are recognised by their ‘target receptors’ in a “lock and key” system. These receptors are usually located in the target cells’ cell membrane, cytoplasm or nucleus. Each hormone (key) fits exactly into its receptor (lock). Only those parts of the body that have the receptor (lock) can respond to the hormone (key). This is why hormones affect some parts of the body, but have no effect on other areas,

Hormones control a range of different functions in the body. These include:

- Bone and muscle health

- Heart function

- Blood pressure

- Metabolic rate

- Sexual development and reproduction

- Growth and development

- Immune system regulation

- Mood

- Attention, learning and memory

- Stress responses

- Sleep cycles

- Appetite and body weight

Some examples of hormonal responses include:

- After a meal, the hormone insulin is released from your pancreas. Insulin helps keep blood sugar levels in a healthy range. Insulin works to unlock the cell membrane, so that the glucose can enter and thus be used by the cell and mitochondria for energy. The thing is, if I am already in dysregulated states, my blood sugars will already be at a high level of activation. This in time may result in insulin resistance. Insulin resistance is when your cells in your muscles, fat, and liver are not responding efficiently to insulin and cannot easily take up glucose from your blood. As a result, your pancreas makes more insulin to help glucose enter your cells. Impaired insulin sensitivity can result in onset Diabetes type 2. Here is how…. Over time, though, insulin resistance will get worse, and the pancreatic beta cells that make insulin can wear out. Eventually, the pancreas no longer produces enough insulin to overcome the cells’ resistance. The result is higher blood glucose levels, and ultimately, prediabetes or type 2 diabetes!

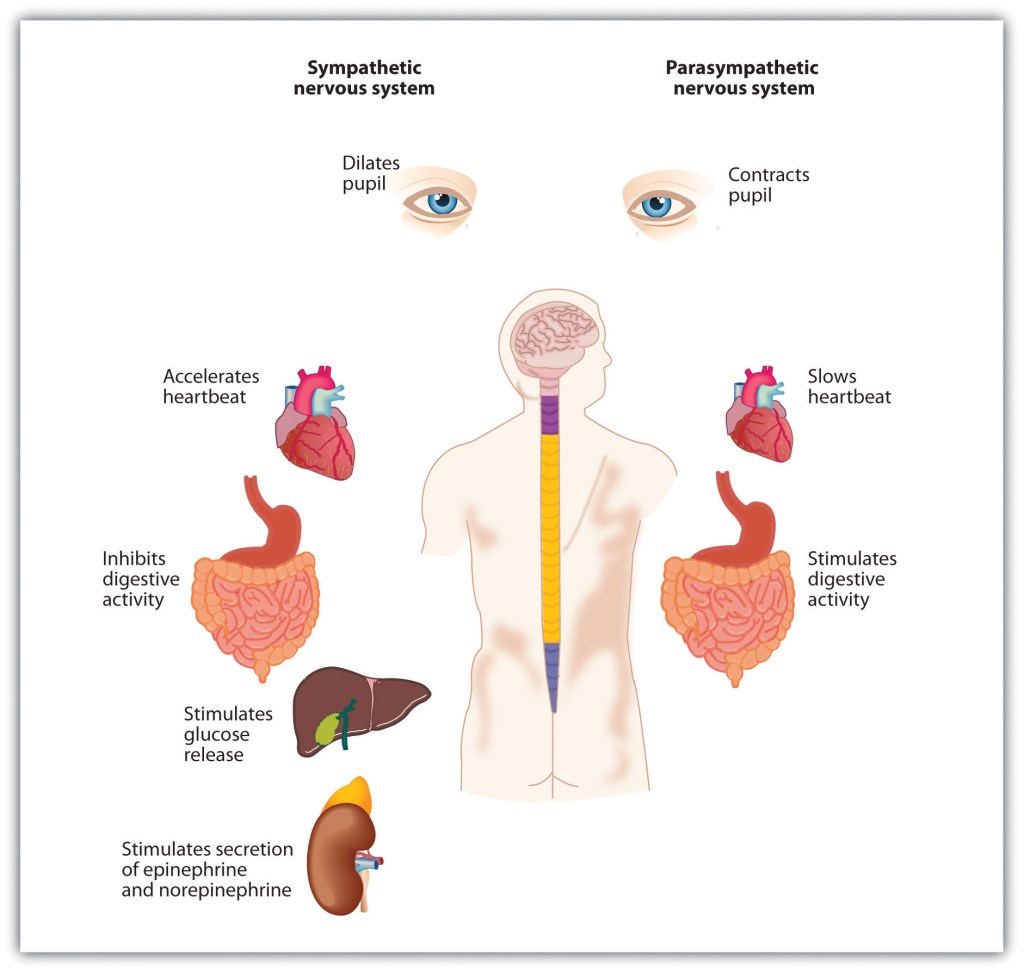

- The adrenal glands produce hormones that regulate salt and water balance in the body, and they are involved in metabolism, the immune system, and sexual development and function. The most important function of the adrenal glands is to secrete the hormones cortisol, epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) and norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) when we are excited, threatened, or stressed. In response to stress, the hormones are released from the adrenal glands, located in the medulla structure of the Kidneys. They signal different parts of the body to prepare for, or escape from, a threat. These hormones act in accordance with the sympathetic division of the ANS, causing increased heart and lung activity, lowered HRV, dilation of the pupils, and increases in blood sugar, which give the body a surge of energy to respond to a threat. The activity and role of the adrenal glands in response to stress provide an excellent example of the relationship and interdependency of the nervous and endocrine systems. A quick-acting nervous system is essential for immediate activation of the adrenal glands, while the endocrine system via hormonal response mobilises the body for action.

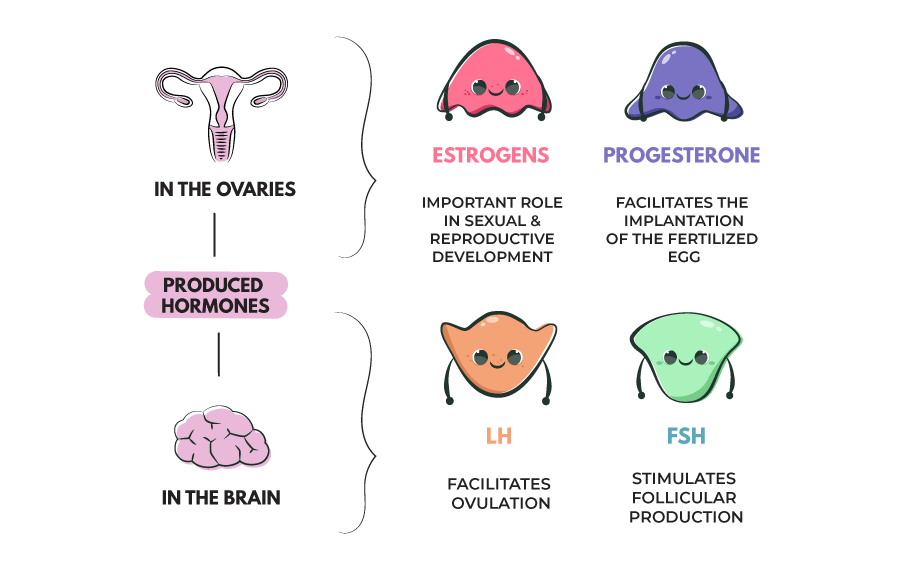

- The ovaries, the female sex glands, are located in the pelvis. They produce eggs and secrete the hormones estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen is involved in the development of female sexual features, including breast growth, the accumulation of body fat around the hips and thighs, and the growth spurt that occurs during puberty stages. Both estrogen and progesterone are also involved in pregnancy and the regulation of the menstrual cycle. Across the menstrual cycle, the hormones progesterone and estrogen are released which help prepare the uterus for fertilisation and child bearing.

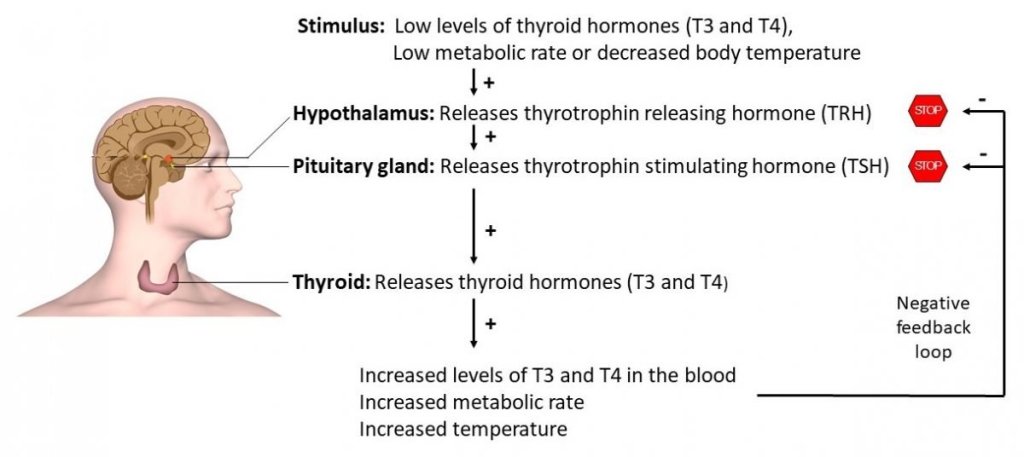

- In response to low thyroid hormone levels, or a low metabolic rate, the hypothalamus in the limbic brain releases Thyrotrophin Releasing Hormone (TRH). The TRH signals the pituitary gland to release Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH). TSH then signals the thyroid to make and release thyroid hormones. This increases the level of thyroid hormone in the blood, which act to increase metabolic rate. When thyroid hormones reach a threshold, the hypothalamus and pituitary stop making TRH and TSH. This feedback loop switches the system off to keep thyroid hormones within a normal range. However, if we are in cyclical mobilised stress response, the conversion of T4 to T3 is slowed down. We can also convert more of our T3 into RT3 rather than FT3. This imbalance puts the brakes on ALL of your metabolic processes, slowing them down and hence can cause thyroid symptoms. (see image below)

If hormones are misaligned, over-active or indeed in a fatigued state, be sure you will physiologically feel it. It is very common amongst clients that hormonal imbalances are present as a direct result of nervous system functionality. The nervous system communicates to the neuroendocrine glands, feeding it electrical and chemical information on which it can act upon – the electrical components of the nervous system and the chemical components of the endocrine system work together. Your endocrine system regulates how much of each hormone is released. But, this missing link is, this has direct involvement from what the nervous system and immune systems are signalling. The endocrine cells trigger hormonal flow based on what your system has been hardwired and programmed to. Meaning, your body operates from a Homeostasis. When the nervous system and immune responses are off alignment, hormone levels will too be out of balance and sync. The body then will not function normally, which offers an internal environment for sickness and diseases to easily flourish and develop.

For instance, ongoing cycles of stress mobilisation and pain response causes endocrine disruption. This causes severe loads of glucocorticoids to release into the bloodstream via the HPA axis, effecting every organ on your body. If not switched off, this drives sympathetic action, giving poorer hormone peaking. It is said scientifically, for women especially, if you are in cyclical states of stress, pain or trauma response, this will absolutely effect the levels and function of your sex hormones (i.e. ovaries and adrenal glands are the main producers of female sex hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, and small quantities of testosterone). It also reverses healthy immune response and effects your inflammation programming, reduces bone density and calcium channels in your muscle bellies and vessels.

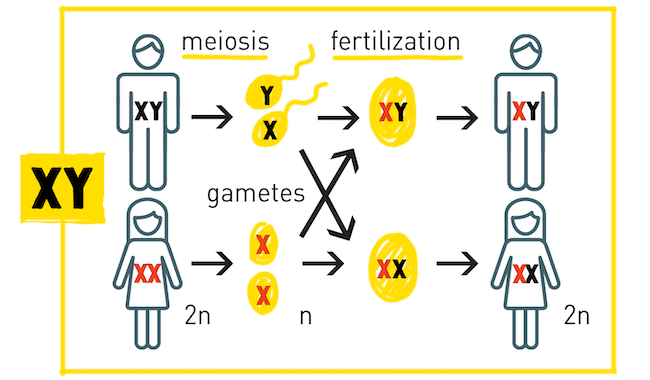

This of course can be an issue if you are trying to conceive, and can effect your chances at fertilisation. Not to mention the cellular and DNA make up that you are hoping to create a child from! It can also inhibit your chances of having a baby girl by 60%! Why? There is much science to it, but in the most simplest terms, XY male chromosomes requires less energy and fuel to develop than XX female chromosomes.

Our everyday activities are controlled by the interaction between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. For example, when we get out of bed in the morning, we experience a rise in cortisol levels and sharp drop in blood pressure if it were not for the action of the sympathetic system, which automatically increases blood flow through the body. Similarly, after we eat a meal, the parasympathetic system automatically sends more blood to the stomach and intestines, allowing us to efficiently digest our food. And perhaps you have had the experience of not being at all hungry before a stressful experience (e.g. job interview, college application, exam), or even feeling nauseous – the sympathetic division is primarily in action here. You might then suddenly finding yourself feeling starved afterward – this is being driven by the parasympathetic thread. The two systems work together to maintain vital bodily functions, resulting in homeostasis, the natural balance in the body’s systems. While the nervous system is designed to protect us from danger through its interpretation of and reactions to stimuli, a primary function of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems is to interact with the endocrine system to elicit chemicals that influence our thoughts, actions, mood, feelings and behaviours.

References

Banks, T., & Dabbs, J. M., Jr. (1996). Salivary testosterone and cortisol in delinquent and violent urban subculture. Journal of Social Psychology, 136(1), 49–56.

Cashdan, E. (2003). Hormones and competitive aggression in women. Aggressive Behavior, 29(2), 107–115.

Dabbs, J. M., Jr., Hargrove, M. F., & Heusel, C. (1996). Testosterone differences among college fraternities: Well-behaved vs. rambunctious. Personality and Individual Differences, 20(2), 157–161.

Gladue, B. A., Boechler, M., & McCaul, K. D. (1989). Hormonal response to competition in human males. Aggressive Behavior, 15(6), 409–422.

Macrae, C. N., Alnwick, K. A., Milne, A. B., & Schloerscheidt, A. M. (2002). Person perception across the menstrual cycle: Hormonal influences on social-cognitive functioning. Psychological Science, 13(6), 532–536.

Mazur, A., Booth, A., & Dabbs, J. M. (1992). Testosterone and chess competition. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(1), 70–77.

Tremblay, R. E., Schaal, B., Boulerice, B., Arseneault, L., Soussignan, R. G., Paquette, D., & Laurent, D. (1998). Testosterone, physical aggression, dominance, and physical development in early adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22(4), 753–777.

Leave a Reply