Trauma isn’t only psychological. It is biological, neurological, and transgenerational. Every experience we go through — every moment of love, loss, safety, or threat — leaves a trace in our nervous system and our genes. Modern science is finally proving what ancient wisdom, somatic traditions, and energy medicine have long known: the body remembers.

Epigenetic science shows that trauma doesn’t end when an event is over; it alters how our genes are expressed — influencing the way our cells behave, how we respond to stress, and how future generations inherit emotional and physiological patterns.

This means that what our ancestors felt and endured — war, migration, famine, displacement, abuse — didn’t disappear with them. It was encoded in their DNA expression, carried through the germline, and continues to influence us today. This is not a metaphor. It’s measurable biology.

The Biology of Trauma

Trauma Changes The Brain. When a person experiences trauma — particularly in early childhood — several key brain regions adapt to help them survive. These include:

- The amygdala, which detects danger, becomes overactive, increasing fear sensitivity and hypervigilance.

- The hippocampus, responsible for memory and contextual understanding, can shrink in size, making it harder to differentiate past from present.

- The prefrontal cortex, which regulates emotion and impulse, becomes under-active, reducing the brain’s ability to self-soothe or think clearly under stress.

These changes have been observed through functional MRI studies in trauma survivors and even in descendants of those who endured severe adversity, such as Holocaust survivors or people born to mothers who were pregnant during war. What this means: the emotional brain becomes dominant, and the rational brain becomes quiet. The nervous system starts to read everyday life as if it’s still inside the original trauma.

Trauma effects the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). The ANS governs our internal sense of safety. It has two main branches:

- The sympathetic system (fight or flight): mobilises energy for action.

- The parasympathetic system (rest, digest, repair): restores balance.

Within the parasympathetic system, the vagus nerve is the key communicator between the brain and the body — running from the brainstem through the heart, lungs, and gut.

According to Polyvagal Theory (Dr Stephen Porges), the vagus nerve operates along a hierarchy:

- Ventral vagal state: safety, connection, social engagement.

- Sympathetic state: mobilisation, anxiety, anger.

- Dorsal vagal state: collapse, freeze, shutdown.

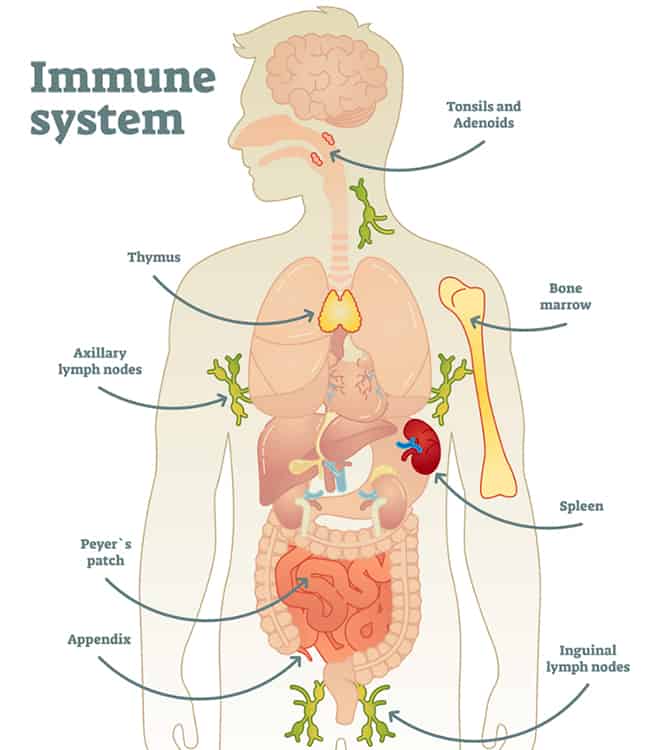

Trauma traps the body in the lower states of this hierarchy — sympathetic arousal or dorsal freeze. As a result, the person’s system becomes dysregulated: digestion, sleep, hormones, and immune function all shift into survival mode. This dysregulation also suppresses vagal tone, which is measurable via heart-rate variability (HRV). Low HRV is now recognised as a biomarker for trauma, chronic stress, and anxiety disorders.

Around 90% of vagal fibres run from the body up to the brain, not the other way around. This means that the body informs the brain far more than the brain instructs the body.

This gut-to-brain feedback forms the gut–brain axis, involving millions of neurons, immune cells, and bacteria. The microbiome itself is shaped by stress hormones and can reflect trauma exposure. Cortisol, adrenaline, and inflammatory cytokines released during stress alter the gut’s permeability — commonly referred to as “leaky gut.” This in turn sends danger signals to the brain, perpetuating anxiety and hyperarousal. Hence, trauma is not “in your head.” It’s a whole-body event mediated by neurochemistry, the immune system, and the microbiome.

The Genetics of Memory

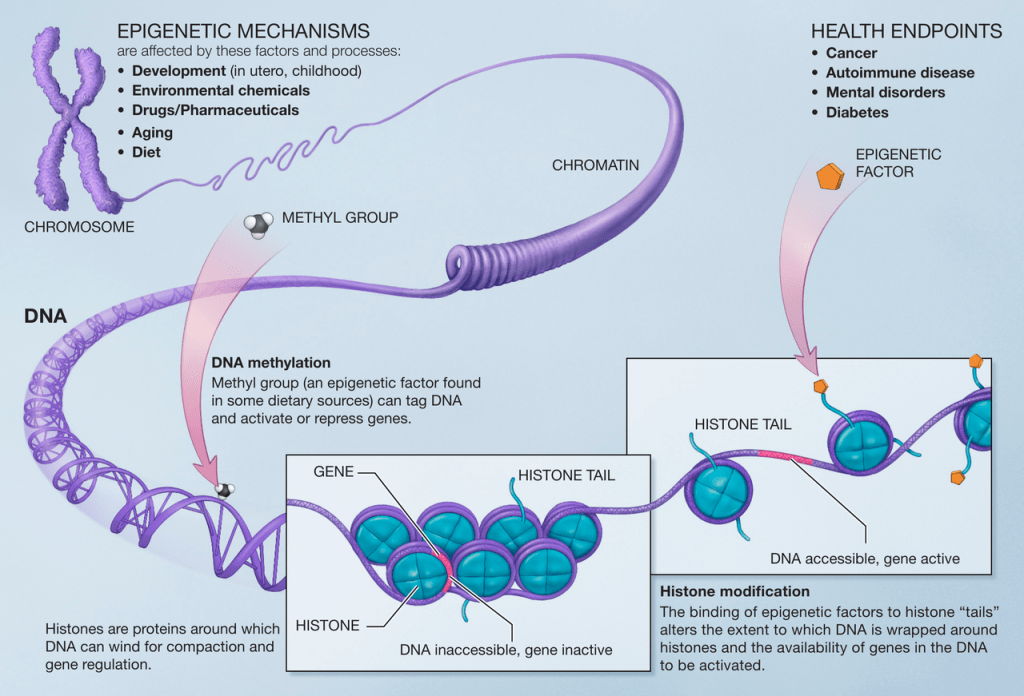

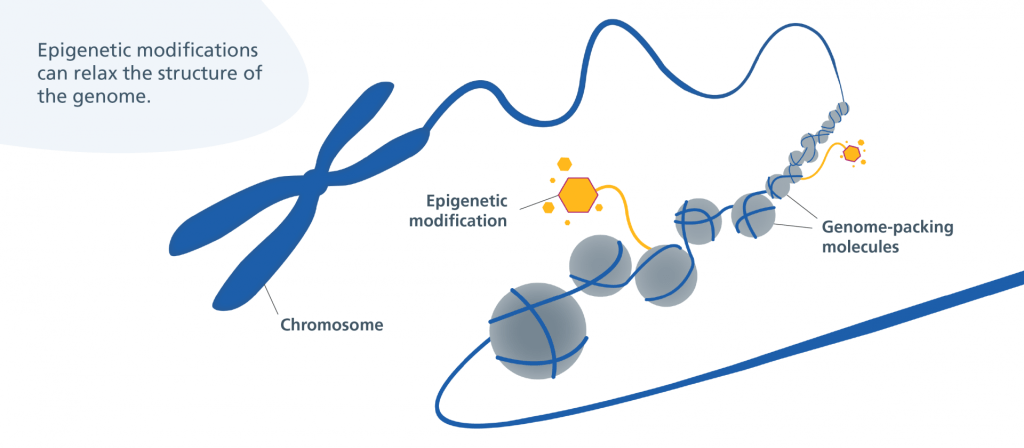

Every cell in your body contains identical DNA — yet different genes are “switched on” in each tissue. The switching process is governed by epigenetic mechanisms such as:

- DNA methylation — the addition of methyl groups that silence or activate genes.

- Histone modification — proteins that package DNA can tighten (silencing) or loosen (activating) access to genes.

- Non-coding RNA — molecules that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally.

Trauma and chronic stress alter these mechanisms. For example, studies have shown:

- Children of Holocaust survivors exhibit methylation changes on the NR3C1 gene, which regulates cortisol sensitivity, making them more reactive to stress.

- Descendants of people who endured famine (e.g. Irish Famine) show altered methylation of metabolic genes, predisposing them to obesity and diabetes.

- Animal studies show that maternal stress changes DNA methylation in offspring for multiple generations, even when the offspring are raised by non-stressed mothers.

This means trauma is biologically inherited, not through DNA sequence but through epigenetic programming — a kind of molecular memory that tells the body how to interpret the world. When we talk about “ancestral trauma,” we are describing these very real biochemical signatures that carry emotional history across time.

Transgenerational Transmission and the Family Nervous System

Epigenetic inheritance is one layer; relational inheritance is another.

A child’s nervous system develops in resonance with the caregiver’s. Through co-regulation, the parent’s tone of voice, eye contact, breathing rhythm, and emotional presence teach the infant’s brain what safety feels like. If the parent’s system is dysregulated due to unresolved trauma, the child’s developing nervous system learns those same stress patterns.

Thus, trauma is passed on both biologically and behaviourally, through nervous system attunement.

Neuroscientist Dr. Allan Schore describes this as the “right-brain-to-right-brain” transmission of emotional regulation. The infant’s limbic system literally wires itself in response to the parent’s.

This is how lineage trauma becomes a living ecosystem within families — a nervous system continuum that can either perpetuate fear or, through healing, transmit safety.

The Womb as Ancestral Interface

For women, the uterus and reproductive organs hold an extraordinary level of ancestral intelligence. During pregnancy, a mother and foetus share a biochemical environment. Research shows that maternal cortisol, inflammatory markers, and emotional state affect the foetal nervous system and gene expression.

Even more astonishingly, when a woman is pregnant with a female foetus, that foetus already contains the immature egg cells that could one day become the next generation. In other words: the grandmother’s biology directly influences the granddaughter’s cellular makeup. Three generations are connected simultaneously through one womb.

This is not just poetic — it’s epigenetic fact. The womb is therefore a biological and energetic bridge between past and future. It holds ancestral memory, not as metaphor, but as methylation patterns, hormonal responses, and cellular imprints. Many women sense this intuitively — the feeling that grief, fear, or shame within the womb is not entirely their own. Healing this space through somatic and energetic work can shift patterns that were embedded long before birth.

The Physiology of Suppression

When trauma occurs and the person cannot fight or flee, the body enters immobility — the freeze state. Neurochemically, this involves surges of opioids and endorphins that numb pain, slow heart rate, and create dissociation. If the body never has the chance to complete the stress cycle (through shaking, crying, running, or vocal release), that energy remains trapped as undischarged autonomic activation. The fascia — our connective tissue network — holds this tension at a cellular level, creating stiffness, inflammation, or energetic stagnation.

Somatic therapies, tremor release, and bodywork allow the nervous system to unwind this stored charge. When the body trembles or releases spontaneously, it’s completing the very action that was interrupted during trauma. This is not regression; it’s repair.

The Neurochemistry of Trauma

Chronic stress and trauma influence neurotransmitters and hormones, including:

- Cortisol and adrenaline — elevated for long periods, causing fatigue, weight changes, and immune suppression.

- Oxytocin — the bonding hormone, often reduced after relational trauma, making connection feel unsafe.

- Serotonin and dopamine — dysregulated, leading to mood disorders or addictive behaviours.

- Inflammatory cytokines — increased systemic inflammation linked to depression, autoimmune conditions, and pain.

Neuroscientists now speak of psychoneuroimmunology — the study of how psychological stress alters immune function and gene expression.

The body and mind are not separate; they are one continuous field of signalling and response.

The Science of Healing

The same brain that was shaped by trauma can be reshaped by safety.

Neuroplasticity — the brain’s ability to form new neural connections — allows us to re-pattern emotional and physiological responses through experience.

Each time you regulate your breathing, ground your body, or self-soothe instead of react, you are strengthening the neural pathways of safety and weakening the old trauma circuits. This process is measurable: trauma therapy and meditation have both been shown to increase hippocampal volume, restore prefrontal activation, and reduce amygdala hyperactivity.

Epigenetic Reversal Through Regulation

Epigenetic marks are not permanent. Research demonstrates that lifestyle and environment can reverse stress-induced methylation patterns.

- Mindfulness and meditation reduce methylation on inflammatory genes such as NF-κB.

- Regular exercise and vagal stimulation upregulate genes linked to neurogenesis and longevity.

- Nutritional compounds such as folate, B-vitamins, and polyphenols (found in plants) act as methyl donors, supporting balanced gene expression.

When we calm the nervous system, we also alter the biochemical soup that bathes our cells. This environment tells the DNA whether to express health or stress. Thus, every act of regulation — rest, movement, connection — becomes molecular medicine.

The Role of Relationship and Co-Regulation

Healing does not happen in isolation. Because trauma is relational, safety must be experienced relationally to be fully restored. The nervous system learns safety through co-regulation — attuned presence, eye contact, rhythm, and compassion. When someone feels deeply seen and met without judgment, their ventral vagal system activates, oxytocin rises, and cortisol lowers. This is why somatic therapy, conscious partnership, and safe community are potent regulators.

Every authentic connection rewires the neurobiology of trust.

From Survival to Evolution

Once the nervous system completes the trauma cycle, energy that was once trapped in survival becomes available for creation. Biologically, this looks like improved HRV, balanced cortisol rhythms, and restored hormonal flow. Psychosomatically, it feels like expansion, intuition, and aliveness. You begin to live from the ventral vagal state — where love, curiosity, and play are possible. Your perception shifts from “What’s wrong?” to “What’s possible?” This is the embodied expression of post-traumatic growth.

Ancestral Healing and Future Generations

Perhaps the most profound discovery in modern epigenetics is that healing is transmissible. Just as trauma can pass down, so can regulation.

When you change your internal environment — calm your vagus nerve, reduce inflammation, live in coherence — the chemical messages in your body change. If you have children, this new biology is reflected in their gene expression and nervous system development.

You become the break in the chain, the place where the lineage begins to tell a new story. Trauma may shape our origins, but it does not define our destiny. The nervous system is plastic, the genome is dynamic, and the human spirit is infinitely regenerative.

In Conclusion

The truth about trauma is both sobering and liberating. It tells us that pain is real, that it imprints the body and echoes through generations — but it also tells us that we are not bound by it. Every breath, every choice to slow down, every act of compassion rewrites the language of your cells.

You are not only healing yourself; you are restoring an entire ancestral field. The body that once carried memory becomes the body that carries light. This is the new biology of consciousness — where science and soul finally meet.

Reference List

- van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking Press.

→ Foundational work on how trauma imprints in the body and brain. - Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

→ Key reference on vagus nerve regulation, safety, and social engagement systems. - Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

→ Introduces the somatic approach to releasing trauma from the nervous system. - Dispenza, J. (2014). You Are the Placebo: Making Your Mind Matter. Hay House.

→ Explores neuroplasticity, gene expression, and mind-body reprogramming. - Lipton, B. H. (2005). The Biology of Belief: Unleashing the Power of Consciousness, Matter, and Miracles. Hay House.

→ Seminal work linking cellular biology and epigenetics with thought and emotion. - Yehuda, R., & Lehrner, A. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: Putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 243–257.

→ Peer-reviewed study showing how trauma markers can be passed through DNA expression. - McEwen, B. S., & Morrison, J. H. (2013). The brain on stress: Vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex over the life course. Neuron, 79(1), 16–29.

→ Details how chronic stress alters neuroplasticity and emotional regulation. - Meaney, M. J. (2010). Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene × environment interactions. Child Development, 81(1), 41–79.

→ Explains how environment and experience modify gene expression through epigenetic regulation. - Szyf, M., McGowan, P., & Meaney, M. J. (2008). The social environment and the epigenome. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis, 49(1), 46–60.

→ Strong academic grounding for how early-life stress can influence DNA methylation patterns. - Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. New York: Guilford Press.

→ Integrates attachment theory, neurobiology, and interpersonal regulation. - Cozolino, L. (2017). The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy: Healing the Social Brain. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

→ Excellent source connecting neurobiology, attachment, and relational healing. - Pert, C. B. (1997). Molecules of Emotion: The Science Behind Mind–Body Medicine. New York: Scribner.

→ Landmark text showing how peptides and emotions form a biochemical network through the body. - Rachel Yehuda (2015). Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past. APA Press.

→ Clinical and biological exploration of trauma’s effects on gene expression and neural circuits. - Jirtle, R. L., & Skinner, M. K. (2007). Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nature Reviews Genetics, 8(4), 253–262.

→ Leading study on how environmental factors influence genetic expression across generations. - Maté, G. (2023). The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture. London: Vermilion.

→ Contemporary integration of trauma, culture, and nervous system dysregulation.

Leave a comment