The nervous system is a living intelligence, quietly orchestrating every aspect of human movement, reflex, and sensation. It is responsible for guiding posture, balance, coordination, and fine motor skills, all while responding to the environment and emotional experiences. Most people do not realise that their nervous system is not simply a biological machine but a living network that reflects their inner world, carrying the memory of past experiences, emotional responses, and protective patterns.

When a person experiences repeated stress, trauma, or chronic pressure, the nervous system adapts in ways designed to protect. These adaptations often remain long after the threat has passed, shaping how the body moves, how reflexes function, and how the person experiences themselves in their own skin. In this way, trauma is not just a psychological experience. It is a somatic one.

The mind, body, and inner self are deeply intertwined. Understanding the role of the nervous system in movement and emotional experience can illuminate why some people feel disconnected from their bodies, why reflexes can be dulled or heightened, and why fine motor control may feel inconsistent. By exploring neuromechanics through a trauma-informed lens, it becomes possible to reclaim fluidity, presence, and ease in everyday life.

The Body Moves in Response to the Nervous System

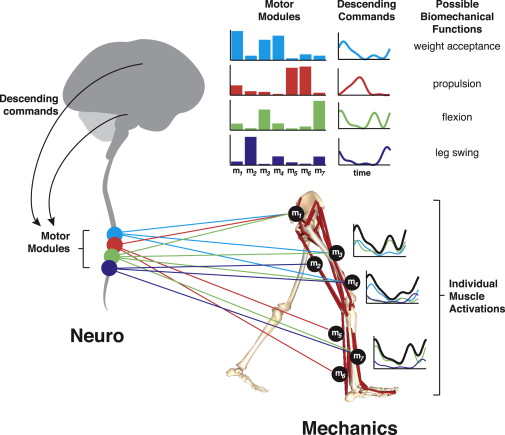

Neuromechanics is the study of how the nervous system controls and organises movement. It encompasses reflexes, motor patterns, coordination, balance, posture, and fine motor skills. At its core, it is the language through which the nervous system communicates with the body, shaping how a person interacts with the world.

Reflexes are automatic responses designed to protect the body. They are the first line of defence, allowing a person to react quickly without conscious thought. Motor neurons transmit signals from the brain and spinal cord to muscles, guiding voluntary movements and fine adjustments. Proprioception, the body’s sense of position and movement in space, ensures that a person can move fluidly, catch themselves if they stumble, and coordinate complex tasks like typing, writing, or playing a musical instrument.

When the nervous system is well regulated, movements are smooth, reflexes respond appropriately, and fine motor skills are precise. When the nervous system is dysregulated due to trauma or chronic stress, these systems become less reliable. For example, a professional in a high-pressure office in Europe or North America may notice shallow breathing, tension in the shoulders, or stiff fingers while typing. A musician in Canada may experience subtle tremors or a loss of fluidity in their hands after months of high stress. These examples illustrate how deeply movement is connected to the state of the nervous system.

The intelligence of the nervous system extends beyond physical coordination. Every movement, posture, and reflex is an expression of the body’s history, both protective and adaptive. Recognising this connection is the first step toward understanding how trauma and stress impact neuromechanics.

Cycles of Trauma and Stress Patterns Shape Your Neuromechanics

Trauma and stress leave imprints on the nervous system that can shape movement and posture in profound ways. These experiences create cyclical patterns in which the body becomes conditioned to anticipate danger, even in safe environments. The fight, flight, or freeze response, once critical for survival, can become a persistent state.

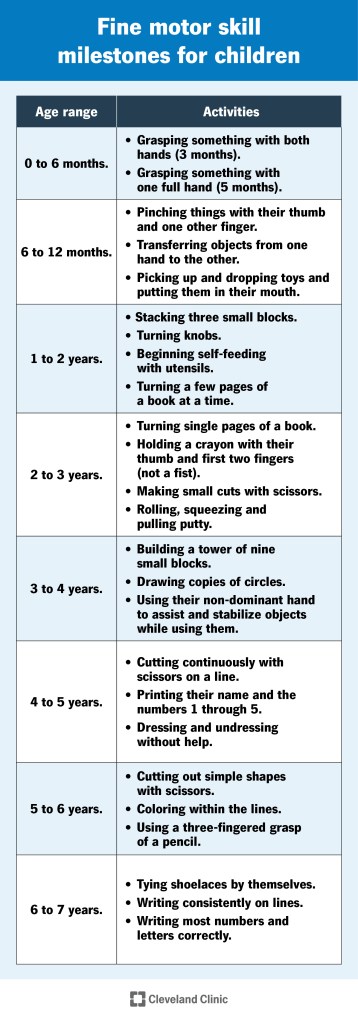

When a person remains in these protective states, muscles may stay chronically tense, joints may become restricted, and reflexes may either overreact or become blunted. Fine motor control, which requires subtle coordination and relaxation, can be impaired. Fine motor control is a complex process that requires:

- Precision (dexterity)

- Awareness and planning

- Coordination

- Muscle strength

- Sensation in your hands and fingers, feet and toes

For example, a person who experiences constant workplace stress may develop tight shoulders, reduced wrist mobility, and shallow breathing that subtly alters hand movements. A university student may notice tremors or stiffness in the hands and tight hips (including Psoas) during seated study sessions (working on the laptop, sitting reading articles) due to prolonged stress patterns. These bodily adaptations reflect the nervous system’s attempt to maintain safety but may inadvertently restrict natural movement.

Childhood trauma or adverse experiences further embed these patterns. The body develops defensive habits that continue into adulthood, shaping posture, reflexes, and neuromechanical fluidity. Jaw clenching, hunched shoulders, shallow breathing, and tight hips are not merely physical complaints but somatic echoes of protective strategies formed during past stress or trauma.

The inner self learns from these experiences as well. Subtle soul language can describe the nervous system as a guardian, continuously striving to keep the person safe. While these adaptations were necessary at one time, they now limit expression, presence, and ease in daily life.

Are You Stuck in a Stress Cycle?

Recognising the impact of trauma on movement and reflexes is essential for healing. Some signs that a person may be stuck in a stress cycle include:

- Chronic tension in the neck, shoulders, jaw, or hips

- Shallow or irregular breathing

- Impaired fine motor coordination, such as difficulty typing, handwriting, or manipulating small objects

- Heightened startle response or exaggerated reflexes

- Feelings of ‘clumsiness’ or imbalance

- Difficulty relaxing or sensing the body in time and space

These signs are indicators of a nervous system that has adapted to protect the person in the face of past stress. By learning to identify these patterns, a person can begin the journey toward regulation and fluidity.

Neuroplasticity and Healing

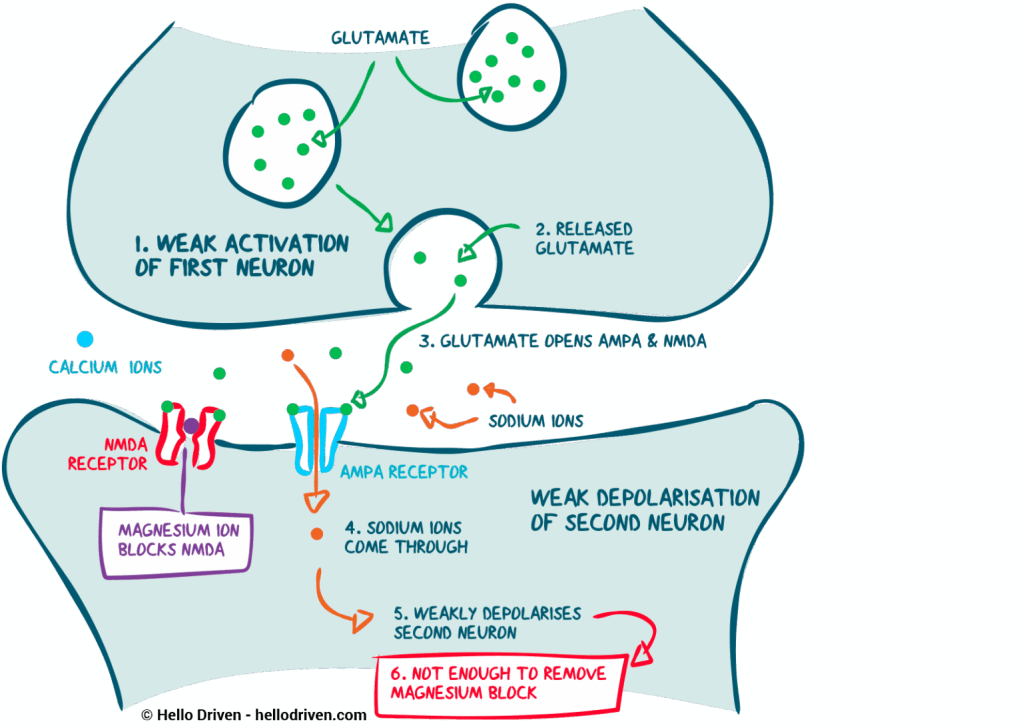

The nervous system is remarkably adaptable. Neuroplasticity allows neural pathways to reorganise in response to experience, learning, and intentional practice.

Trauma and stress alter these pathways, but the same capacity for change enables healing and restoration. The prefrontal cortex, cerebellum, brainstem, and vagus nerve are central to regulating movement, reflexes, and emotional responses. Through repeated practice, safe experiences, and mindful movement, these systems can be retrained. For example, gentle exercises that involve slow hand movements, mindful posture adjustments, or somatic awareness can strengthen neural connections that support precise and fluid movement.

Trauma-informed approaches acknowledge that the nervous system requires safety and guidance to rewire effectively. By creating supportive conditions, the nervous system can learn to release unnecessary tension, refine reflexes, and restore natural neuromechanical patterns. The body and inner self can once again function in harmony, reflecting intelligence, presence, and vitality.

Regulation as the Foundation of Repatterning

Before meaningful changes in neuromechanics can occur, the nervous system must be regulated. Regulation involves balancing activation and relaxation, allowing the nervous system to respond appropriately rather than react automatically.

Top-down regulation refers to the influence of the mind on the body. Practices such as mindfulness, guided awareness, and cognitive reframing help the brain send calming signals to muscles and organs. Bottom-up regulation refers to signals from the body to the brain. Gentle movement, breathwork, and somatic awareness provide feedback that informs the nervous system of safety and presence. Co-regulation, or relational safety, reinforces these processes, showing the nervous system that connection and presence are secure. Through regulation, the inner self can reclaim a sense of embodiment. The body becomes a trusted guide rather than a site of restriction or tension. Fluidity, coordination, and ease begin to return.

Vagus Nerve Tone & Nervous System Communication

The Vagus Nerve s a primary pathway for nervous system regulation. The vagus nerve communicates signals between the body and brain, influencing heart rate, reflexes, digestion, and emotional state. Slow, intentional breathing activates the parasympathetic system, promoting relaxation, fluid movement, and improved reflex function.

Simple practices such as slow exhalation, gentle humming, or noticing the expansion of the belly during breath can enhance vagal tone. Breath becomes a bridge between the body and inner self, allowing the nervous system to settle and movement to flow with ease.

Restoring neuromechanics is not purely physical. When the nervous system is regulated, the mind and inner self experience clarity, presence, and emotional balance. Embodied awareness fosters creativity, resilience, and confidence. Daily life becomes an opportunity to reconnect with the body and the inner self. Mindful walking, noticing posture while standing or sitting, and gentle hand movements are simple ways to maintain this connection. Each moment of awareness reinforces the integration of mind, body, and soul.

Practical Tips to Restore Neuromechanics & Safety

- Observing posture throughout the day and adjusting

The first step in restoring healthy neuromechanics is awareness. Spend a few moments each day noticing posture while sitting, standing, or walking. Observe tension in the shoulders, neck, jaw, and hips. Gently adjust the spine, allow the shoulders to soften, and lengthen the neck. This small daily habit helps the nervous system recognise patterns of safety, releases habitual tension, and improves proprioception, which is the sense of where the body is in space.

2. Practising mindful breathing exercises

Intentional breathing is one of the most effective ways to regulate the nervous system. Practices such as slow diaphragmatic breathing, extending the exhale, or gentle humming stimulate the vagus nerve, activating the parasympathetic nervous system. When the nervous system is in a state of balance, reflexes, coordination, and fine motor skills improve. Simple exercises include inhaling for four counts, holding for two counts, exhaling for six counts, or taking short pauses to notice the rise and fall of the belly.

3. Performing micro-movements, nerve flossing, active and dynamic mobility exercises

Small, intentional movements retrain reflexes and restore mobility while engaging the nervous system in safe and effective ways. These include micro-movements, which are subtle adjustments such as slowly flexing and extending the fingers, gently rotating the wrists, or shifting weight while standing. Nerve flossing can be incorporated into these practices, using gentle, controlled movements to mobilise specific nerves along their pathways, release tension, and restore neural communication. Examples include straight-leg lifts with ankle flexion for the sciatic nerve or wrist and finger stretches to improve radial and median nerve mobility.

Active and dynamic mobility exercises complement these techniques by guiding the body through controlled movements across a full range of motion. Slow arm circles, hip swings, and mindful spinal twists not only increase joint flexibility and circulation but also reinforce coordination and body awareness, enhancing reflexes and fine motor control.

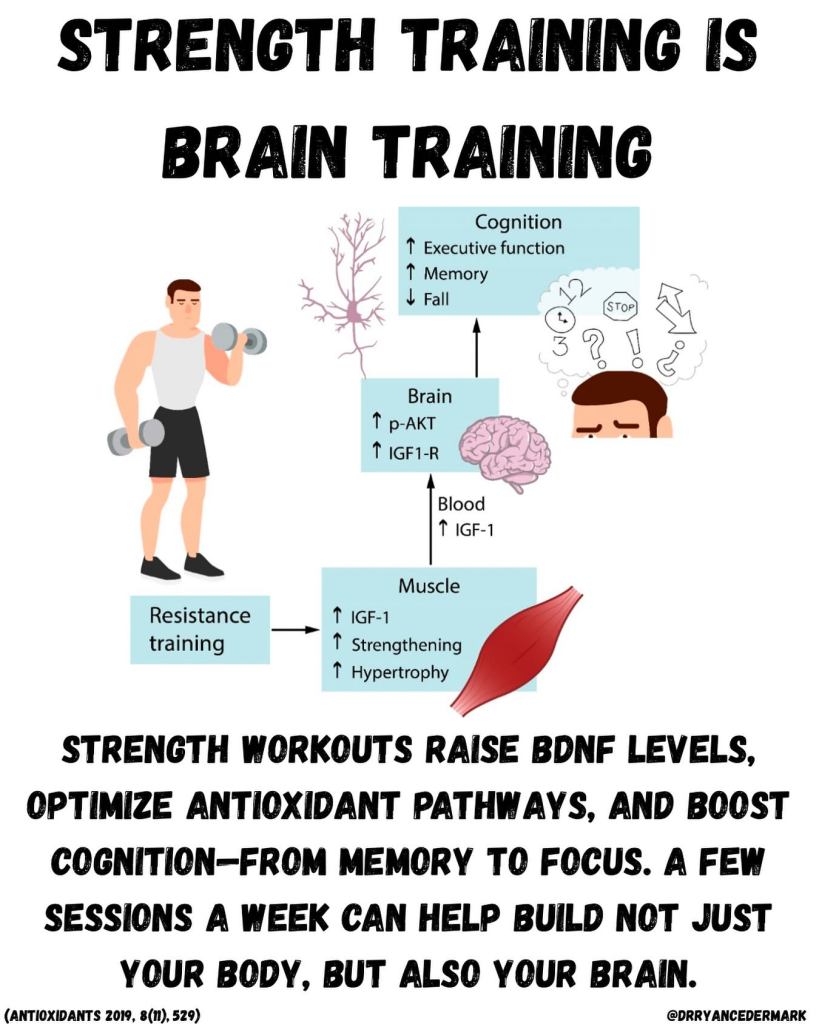

4. Incorporate weight lifting

Weight training is not solely about building muscle or aesthetics. It is a powerful tool for improving neuromechanics, reflexes, posture, and nervous system regulation. Resistance training engages multiple systems simultaneously:

- Muscle Activation and Coordination: Weight training requires the nervous system to coordinate muscles efficiently, enhancing reflexive patterns and improving fine motor control.

- Posture and Joint Stability: Exercises like squats, deadlifts, or overhead presses strengthen the stabilising muscles around the spine, shoulders, and hips, reducing habitual tension and enhancing alignment.

- Stress Regulation: Resistance training triggers controlled stress that allows the body to learn recovery. The nervous system adapts to manageable challenges, improving resilience and reducing hypervigilance associated with trauma.

- Proprioception and Body Awareness: Lifting weights with mindful attention enhances the sense of where the body is in space, improving balance, coordination, and movement fluidity.

When integrating weight training, start with lighter resistance and focus on form, controlled movement, and muscle-mind engagement. Include compound movements that recruit multiple muscle groups, such as:

- Squats and lunges for lower body and core stability

- Rows and presses for upper body strength and postural support

- Deadlifts and hip hinges for posterior chain engagement

- Shoulder movements for range of motion and reflex integration

Perform 3 sessions per week, incorporating rest days to allow the nervous system to integrate the new patterns. Emphasise breathing and intentional engagement of muscles to enhance the mind-body connection during each exercise.

- Taking short pauses to notice tension and release through movement

- Engaging in mindful breathing that emphasise body awareness

- Reflecting on moments of tension to identify protective patterns

The nervous system is the key to how humans move, feel, and relate to the world. Trauma and stress create patterns that can restrict movement, dull reflexes, and disrupt the connection between body, mind, and inner self. Through regulation, somatic movement and awareness, the nervous system can be repatterned. Neuromechanics can be restored, allowing movement to reflect resilience, ease, and presence. Honouring the mind, body, and soul as an integrated system opens the path to embodied living. Every subtle shift, every breath, every mindful movement brings the inner self into alignment with the body, creating the conditions for fluid, authentic, and empowered presence in life.

References

- van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. Norton

- Levine, P. A. (2015). Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past. North Atlantic Books

- Siegel, D. J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. Guilford Press

- Damasio, A. (2018). The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures. Pantheon

- Craig, A. D. (2002). “How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(8), 655–666

- Sterling, P. (2012). “Allostasis: A model of predictive regulation.” Physiology & Behavior, 106(1), 5–15

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). “Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain.” Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904

- Critchley, H. D., & Harrison, N. A. (2013). “Visceral influences on brain and behavior.” Neuron, 77(4), 624–638

- Fuchs, T., & Koch, S. C. (2014). “Embodied affectivity: On moving and being moved.” Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 508

Leave a comment