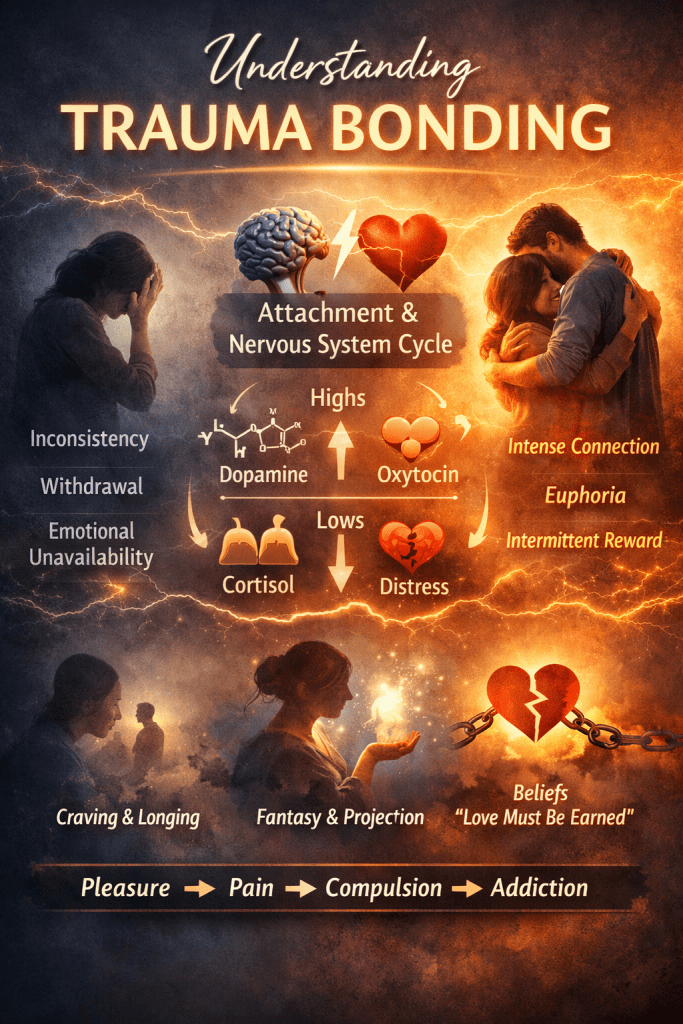

Trauma bonding goes beyond simply being in a difficult or unhealthy relationship. It is a nervous system and brain based cycle that keeps individuals emotionally, cognitively, and physiologically hooked, often despite clear evidence of harm, instability, or emotional unavailability. At its core, trauma bonding reflects how deeply human beings are biologically wired for connection, and how early attachment experiences shape our expectations of intimacy, safety, and love.

Rather than being a failure of insight, boundaries, or self respect, trauma bonding is an adaptive survival pattern. It develops when connection, care, or intimacy are paired with inconsistency, unpredictability, threat, or withdrawal. Over time, the nervous system learns to associate closeness with both relief and danger. This pairing creates a powerful loop that is difficult to exit without addressing the attachment and regulatory mechanisms beneath the behaviour.

This is why trauma bonding often persists even when someone intellectually understands that a relationship is harmful. These patterns are not driven primarily by conscious choice, but by implicit memory, autonomic conditioning, and survival circuitry shaped early in life.

Attachment as a Developmental and Nervous System Blueprint

Attachment theory offers one of the most robust frameworks for understanding trauma bonding. Originally developed by John Bowlby and expanded by Mary Ainsworth and subsequent researchers, attachment theory describes how infants rely on caregivers not only for physical survival, but for emotional regulation and nervous system organisation. From the earliest months of life, the infant’s brain and autonomic nervous system develop in constant interaction with caregivers.

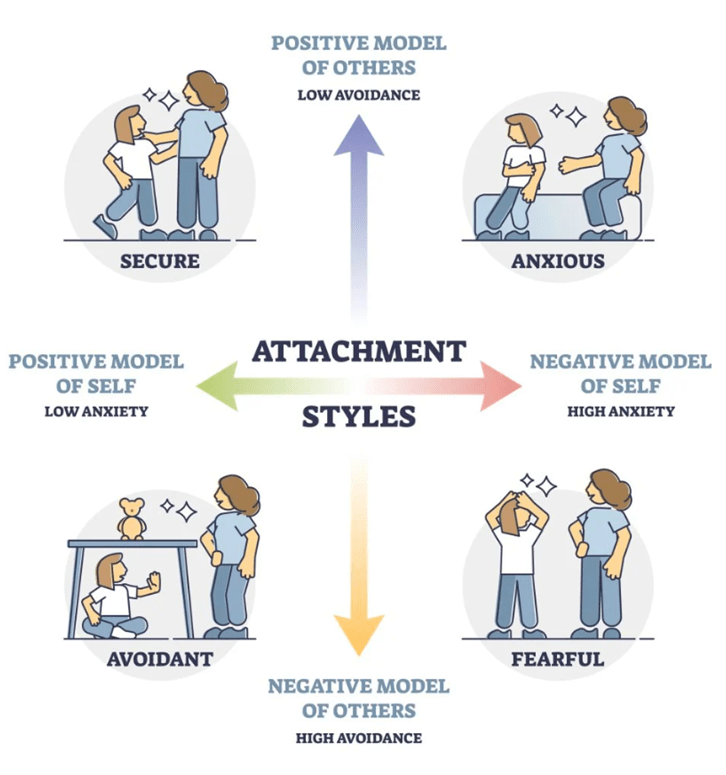

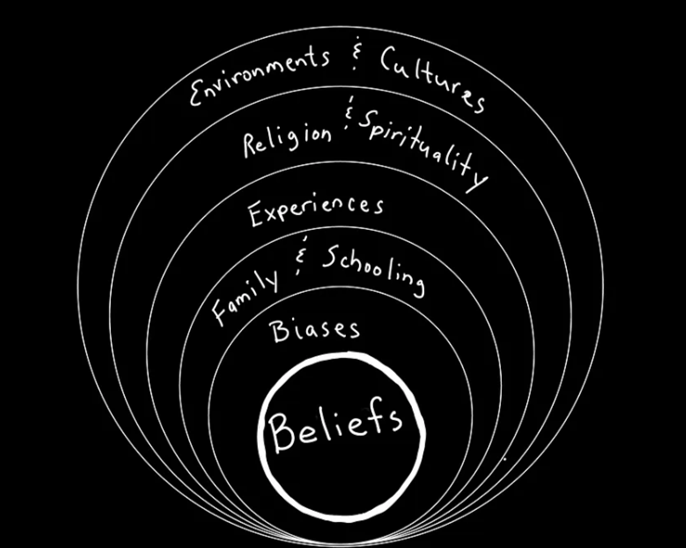

Through repeated cycles of need, response, and repair, children form internal working models of self and others. These models answer fundamental questions: Are my needs welcome? Can I rely on others? Is closeness safe? Am I worthy of care? These answers are not stored as conscious beliefs, but as embodied expectations encoded in the nervous system, limbic system, and procedural memory.

Secure attachment develops when caregivers are consistently responsive, emotionally present, and capable of repairing misattunement. In these environments, the child’s nervous system learns that distress can be soothed, that emotions are tolerable, and that connection is reliable. The body learns safety through repetition.

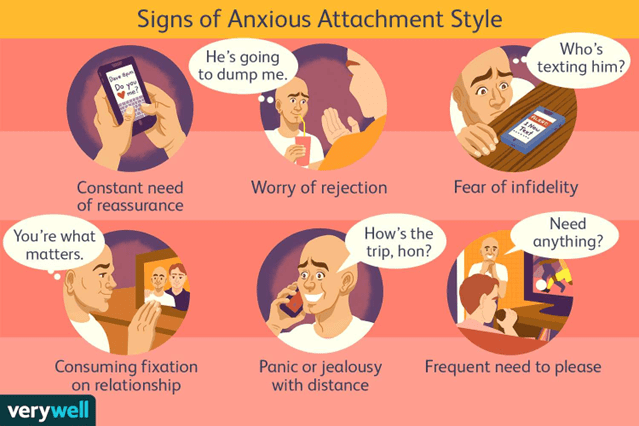

In contrast, insecure attachment strategies emerge when caregiving is inconsistent, neglectful, emotionally unavailable, intrusive, frightening, or unpredictable. Anxious attachment develops when connection is unreliable, leading the nervous system to hyperactivate in order to maintain proximity. Avoidant attachment develops when caregivers dismiss or minimise emotional needs, leading the nervous system to suppress attachment signals. Disorganised attachment arises when the caregiver is simultaneously a source of comfort and fear, leaving the nervous system without a coherent strategy.

These attachment patterns are adaptive responses to early environments. However, they continue to shape relational behaviour into adulthood, particularly under stress, vulnerability, or emotional intensity.

Nervous System Attunement and the Foundations of Regulation

Attachment is fundamentally a nervous system process. Infants are born without the capacity for self regulation and rely on caregivers for co regulation. This occurs through nervous system attunement, including facial expression, tone of voice, eye contact, timing, touch, and emotional presence. When caregivers accurately perceive and respond to the child’s internal state, the nervous system learns regulation and safety.

Misattunement is inevitable in all relationships. What matters is repair. When caregivers can notice misattunement and re establish connection, the child’s nervous system learns flexibility and resilience. When misattunement is chronic, unpredictable, or unrepaired, the nervous system remains vigilant and learns to anticipate threat or loss of connection.

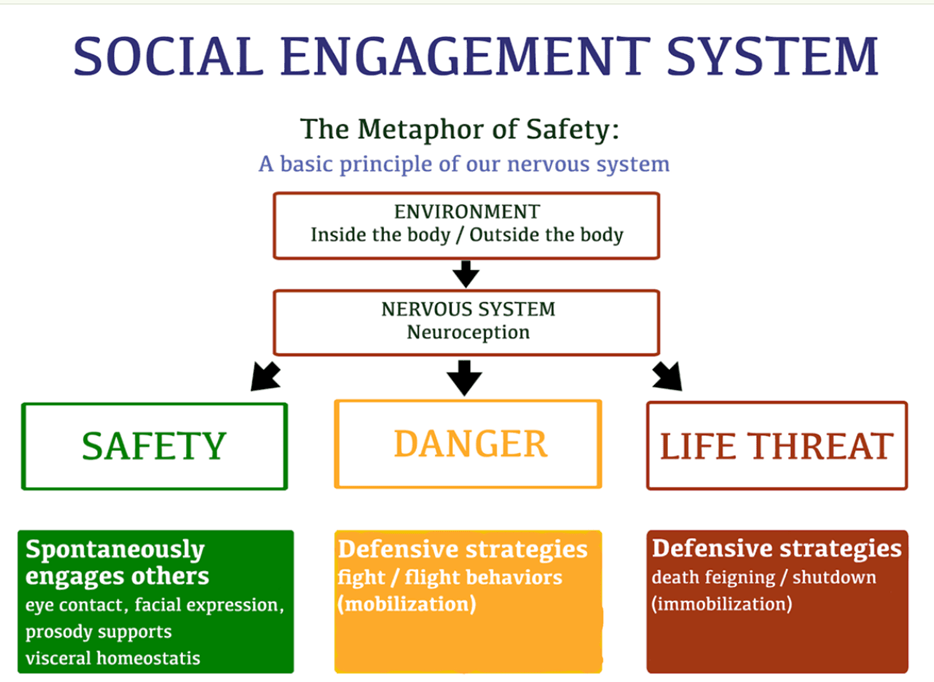

These early regulatory patterns shape how adults experience intimacy. Trauma bonding is driven by cycles of attunement and misattunement that mirror early attachment environments. Moments of closeness, validation, or emotional resonance activate the ventral vagal system, creating sensations of calm, safety, and belonging. When that connection is withdrawn or becomes unpredictable, the nervous system rapidly shifts into survival states.

Sympathetic activation brings anxiety, hypervigilance, urgency, and pursuit behaviours. Dorsal vagal responses may bring collapse, emotional numbing, shutdown, or dissociation. The nervous system oscillates between relief and threat, reinforcing attachment seeking and dependence on the relationship for regulation.

Polyvagal Theory and the Nervous System Ladder

Polyvagal theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges, provides a framework for understanding how these shifts occur. According to this model, the autonomic nervous system operates through three primary states. The ventral vagal state supports safety, connection, and social engagement. The sympathetic state supports mobilisation through fight or flight. The dorsal vagal state supports immobilisation through shutdown or collapse.

In trauma bonded relationships, nervous systems move rapidly up and down this ladder. Moments of connection allow brief access to ventral vagal regulation. Withdrawal or unpredictability triggers sympathetic activation or dorsal shutdown. The nervous system becomes conditioned to this oscillation, mistaking the relief of regulation for intimacy itself.

Over time, calm and consistency may feel unfamiliar or even unsafe, while intensity and unpredictability feel meaningful and alive. This is not a preference, but a conditioned nervous system response.

The Neurobiology of the Push-Pull Cycle

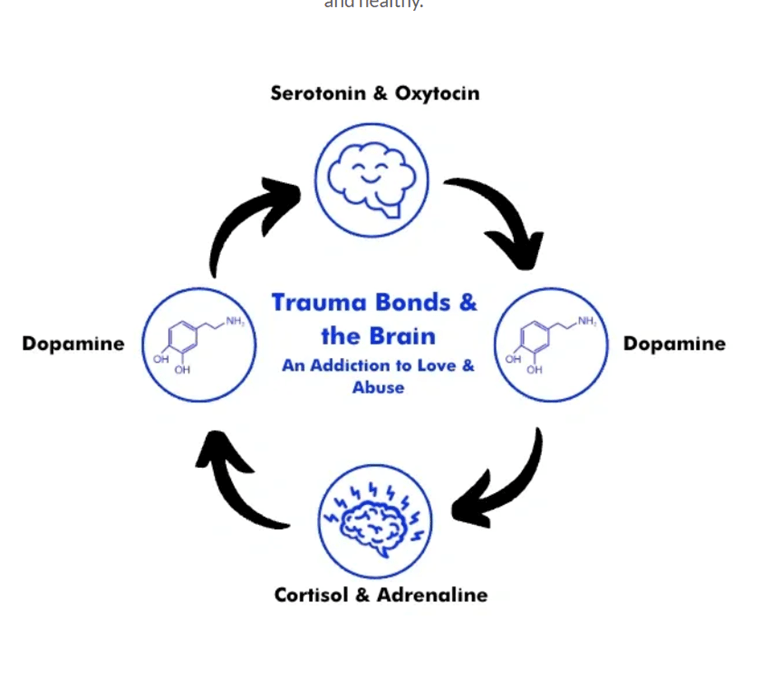

Trauma bonding is sustained by powerful neurochemical processes involving both reward and pain pathways. Dopamine plays a central role in motivation, anticipation, and craving. In relationships characterised by inconsistency, dopamine release is amplified through intermittent reinforcement. Unpredictability strengthens learning and attachment, keeping attention locked onto the attachment figure.

Oxytocin is released during moments of closeness, vulnerability, and emotional intimacy. While oxytocin supports bonding and trust, it does not discriminate between safe and unsafe relationships. In trauma bonded dynamics, oxytocin deepens attachment even when the relationship is destabilising, making separation feel physiologically threatening.

When connection is withdrawn or abandonment is perceived, stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol flood the system. Social rejection and attachment loss activate neural circuits associated with physical pain. This pain drives rumination, longing, and compulsive attempts to restore connection.

The alternation between dopamine driven anticipation, oxytocin mediated bonding, and stress induced pain creates a cycle that closely mirrors addiction. There is craving, withdrawal, tolerance, and compulsion. Intensity becomes confused with intimacy, and relief becomes confused with love.

Limerence, Idealisation, and Fantasy Projection

Psychological processes further intensify trauma bonds. Limerence is a state of intense infatuation characterised by intrusive thoughts, idealisation, longing, and emotional dependency. In limerence, the brain becomes preoccupied with the attachment figure, filtering information through desire and hope rather than reality.

Fantasy projection plays a central role. Unmet childhood needs, attachment longings, and hopes for repair are unconsciously projected onto the partner. Moments of connection are magnified, while inconsistencies are rationalised or minimised. The partner becomes symbolic, representing the possibility of healing early wounds.

This process is not deliberate or naive. It is driven by implicit memory systems and survival circuitry attempting to resolve unresolved attachment pain.

Belief Systems and Cultural Conditioning

Underlying trauma bonding are deeply held belief systems shaped by early caregiving and broader cultural narratives. Children learn not only how relationships function, but what love is supposed to feel like. In many families and cultures, love is associated with sacrifice, emotional labour, endurance, or intensity. Calm, consistent connection may be framed as boring, weak, or undeserved.

Beliefs such as love must be earned, closeness is fragile, or intensity equals intimacy become embedded in the nervous system. These beliefs guide perception, attraction, and behaviour in adulthood, drawing individuals toward familiar relational dynamics even when they are destabilising.

Trauma bonding is therefore reinforced by both physiological conditioning and cognitive meaning making.

Avoidant, Anxious, and Disorganised Pairings

Trauma bonding commonly emerges in pairings between anxious and avoidant attachment styles, or where disorganised attachment is present. Anxiously attached individuals are driven by proximity seeking and fear of abandonment, while avoidantly attached individuals manage closeness through distancing and emotional suppression.

This dynamic creates a self reinforcing loop. The anxious partner pursues connection, activating the avoidant partner’s nervous system and triggering withdrawal. The withdrawal intensifies the anxious partner’s stress response, increasing pursuit. Both nervous systems are dysregulated, yet bonded through the cycle.

Disorganised attachment adds further complexity, as individuals may oscillate between anxious pursuit and avoidant withdrawal, blending into the attachment style of the person in front of them. Identity, boundaries, and emotional coherence may become unstable within the relationship.

Relational Reenactment and Attempts at Repair

At a deeper level, trauma bonding represents neurobiological reenactment. The adult nervous system attempts to resolve unresolved childhood attachment wounds by recreating familiar relational dynamics. The partner becomes a stand in for early caregivers, and the relationship becomes an unconscious attempt at repair.

Each reunion carries hope that this time the outcome will be different. This hope sustains the cycle, even as the pattern repeats.

Healing Trauma Bonds and Reattuning the Nervous System

Healing trauma bonding requires addressing nervous system regulation, attachment expectations, and belief systems simultaneously. Insight alone is insufficient, as these patterns are encoded somatically and implicitly.

Effective healing pathways include nervous system regulation practices, somatic work, interoceptive awareness, and repeated experiences of safe, consistent connection. Over time, the nervous system can learn that calm does not equal danger, that intimacy does not require threat, and that regulation can come from within.

As the nervous system reattunes to safety, attachment patterns can soften. Choice returns. Relationships shift from survival based dynamics toward presence, reciprocity, and authenticity.

Trauma bonding is not a life sentence. With understanding, support, and regulated connection, it is possible to move from addictive relational cycles toward secure, embodied relationships that feel stabilising, expansive, and free.

Leave a comment